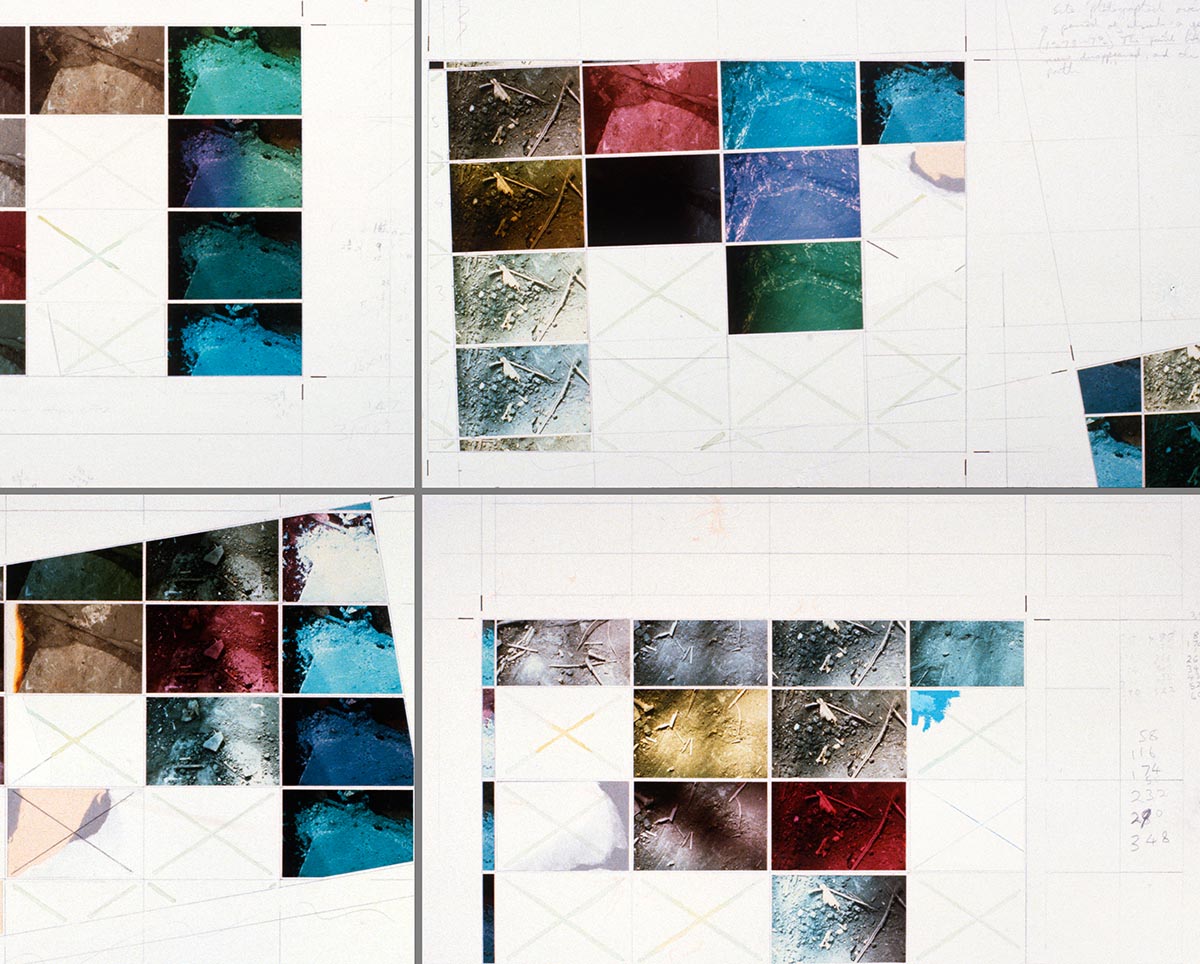

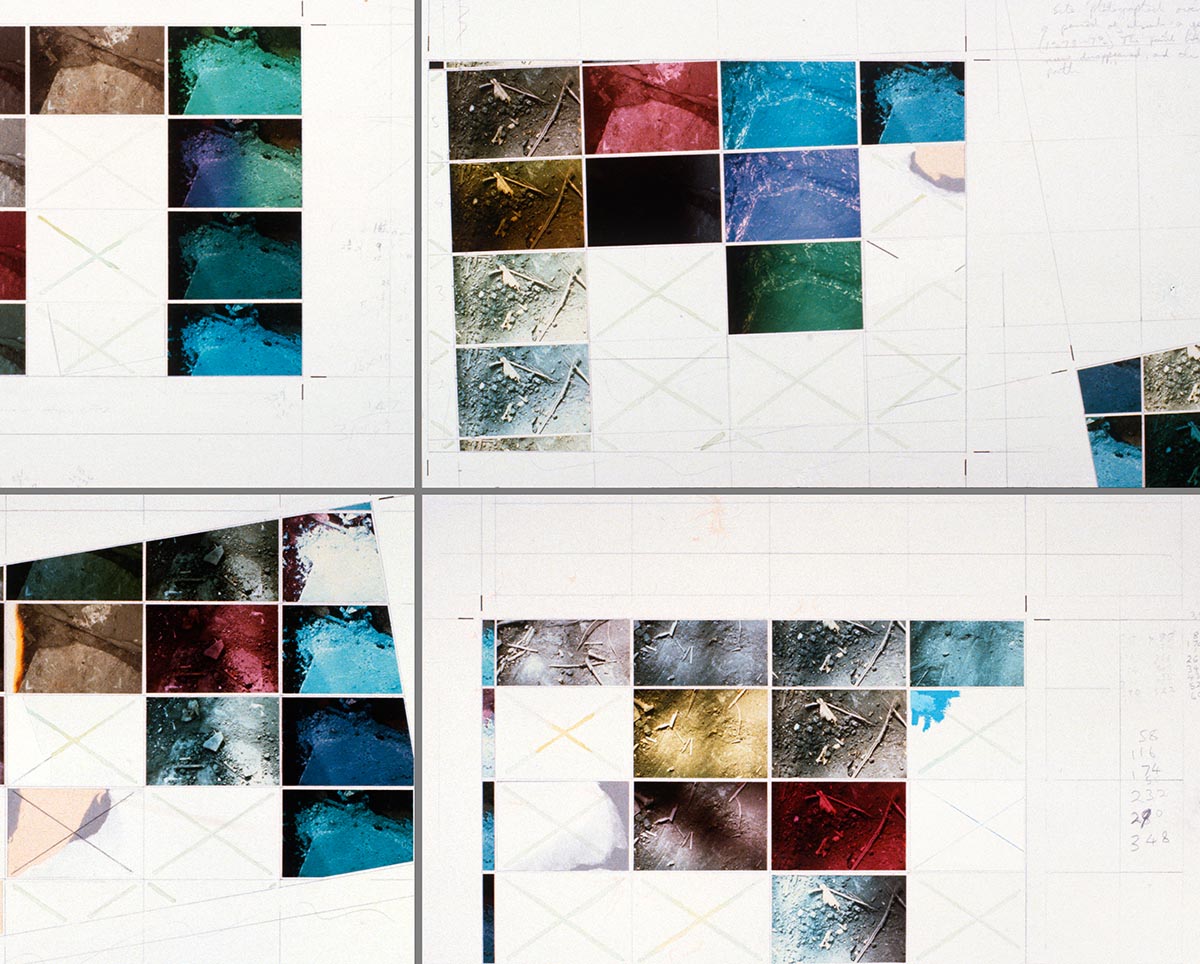

Site/Time/Sectioned or, possibly, The One True Path (detail).

1978-1981

I first encountered Leonardo di Faccia, although he was then just plain Leonard Facey, in 1975 on a ward attached to the Odontology department of Southampton Hospital. When the porters came to take me to the operating theatre they looked at the chart at the bottom of the bed and asked "Leonard Facey?". Although rather relaxed by the pre-med, I had the presence of mind to say "No, he must be in the next bed. My name's White". But the next bed was empty. Leonard, whoever he was, must have already been taken for his operation and I remember hoping that the mis-attribution of bed occupancy had been noticed for him. It seemed like only moments later that I found myself in the recovery room, floating in a seething haze of anaesthesia, staring at the pale green ceiling and the cascading and swirling fluorescent lights. Suddenly I was aware of Leonard's presence, and at that moment a rapport - a meeting of minds - immediately sprang to life. A large Jamaican nurse stood between our trollies and quieted us with matronly firmness "Hey, what are you arguing about? Is it a girl? Calm now, calm". The next thing I remember was the insipid light of a Southampton dawn as I woke to the noise and bustle of a busy teaching hospital ward at 5.30am. I became aware that the next bed was still empty: Leo was then, and I guessed would always remain, a long way ahead of me.

I might have completely forgotten this meeting, but two years later Leonard turned up again. After graduating from Winchester School of Art, a group of us got together to rent a derelict terraced house in Staple Gardens to use as studio space. Now living in London, I would travel down every Friday evening to work in the tiny photographic darkroom that I set up at the top of the stairs. One weekend I was told that a new tenant had taken the rather damp basement. He wasn't an ex-Winchester student but had studied law at Southampton University and wanted space to pursue his interest in minimalism, music and performance art, his name was Leonard. Our paths didn't cross for a few weeks but one Friday just after 10pm, as I was rocking my plastic developing tray and watching the deep blacks and rich greys of my images come to life, I became aware of the sound, almost imperceptible, of someone attempting to play the flute. Such a variety of notes: disjointed, stuttering, and then slow, low and sustained, tentative trills, then suddenly sharp and assertive, but all seeming to come from a very long way away. At 11.00 pm it stopped. There was silence and, shortly after, a gentle tapping on my door. Leo came in and although we had never looked each other in the face before, there was an immediate recognition. He perched in the corner on an old metal filing cabinet and in the orange light of the photographic safelight his red hair and mediterranean complexion seemed to merge into the white emulsion walls so that as we talked he became, in my peripheral vision, rather like a figure in the Parthenon Frieze.

The next Friday evening, as I arrived at the studios, I noticed a strange phenomenon. From the front door you could see down the stairs into the basement and on the wall of the staircase what looked like a slogan had been written. From the doorway I could clearly read:

But the words seemed to float, hanging in the air, unreal, magical, even sinister. Puzzled for a moment, I took a few steps forward, then stood on the stairs and realised that the writer was playing the same trick that Hans Holbein plays in "The Ambassadors". Standing directly in front of them, close up, the written words were a barely readable scrawl, it was only from a distance and an oblique angle that they jumped, like Holbein's Memento Mori, into life. Then I noticed that, in plain and clear writing this time, on the door of Leo's basement studio was written:

Like many enthusiasts who start off with little or no interest in a subject Leo, had been galvanised by one particular event. In one of our last conversations, one that I recorded in 2018, I reminded him of his graffiti and asked where the words had come from:

LdiF: Most of the things I wrote were quotes from Robert Morris, although there were others. They were a sort of 'aide-memoire' on the way to my studio, no one objected, or even mentioned them at the time. I kind of liked the way I could make the words going down the stairs sort of float in the air, so they were real and unreal at the same time.

PFW: I found that a bit disturbing. I also remember "Avoid allusion" and "Labour is not an index of value" or something like that. But why Robert Morris?

LdiF: Do you want the whole story?

PFW: If you like...

LdiF: We came to England in 1969 when I was seventeen. It was really difficult for me, but my family just had to leave Sicily. I should have been going to University to study law, my father was a lawyer, although the family were all farmers. We had money, some, but my English wasn't good enough and I was too disturbed, adrift, to get my A-Levels here. So after school I had to study and do retakes for a couple of years. I'd kept in touch with one girl who'd kind of befriended me in that year and a half I had at school. She'd been very kind to me when I was really struggling. She went off to London to study medicine, but we used to write. I told her that I had never been to London and she said "Why don't you come up? You can sleep on my couch..." So I went. London was nothing like I had expected. I thought it would be all busy and loud and cramped, narrow streets and tall dark buildings, and the air would stink, and everyone would be cold and unfriendly. But it was so spacious and relaxed, and people were nice to me. You know, I'd been brought up to always think before I spoke. Think who might hear, who might pass on what you said, how it would look, how you must not offend, show respect....but these people just said what they thought and laughed a lot. Then she took me to the Morris exhibition at the Tate Gallery.

PFW: When was that?

LdiF: April, I think, a couple of weeks after Easter, 1971.

PFW: I saw that show. The one that got wrecked by the public. We went on a school trip, but after it had reopened, without the audience participation part.

LdiF: I went three times, the first was when you could still get involved and balance on the sheet of wood with the half ball underneath and fall off the beam, drag the weights, you know? It was a revelation. I thought art was all about deep meaning, and fine skill, and using expensive oil paints, gilded frames, beauty and religion and all that stuff. At school they tried to make you do linocuts of characters from the Commedia Dell'arte. So part of me thought these mirrored cubes, and the hanging felt, and the big plywood shapes, were just stupid. But it got to me, I couldn't stop thinking about it. We went back when you weren't allowed to play anymore, so we sat on the floor in the middle of the mirror cubes and just laughed. That first weekend it was one epiphany after another. London was not how I had imagined it. I discovered that people did not behave as I thought they had to. You could think and speak in a way that I had not known was possible. Art was not what I thought it was....and she didn't have a couch.

PFW: I suppose I might have guessed that.

LdiF: I think I understood that weekend that physicality, thought and feeling went together, were all important, all part of the same... But then, and for years after, I found out as much as I could about Morris. Read all the things he'd written, copied out phrases and tried to remember them. Of course, my epiphanies soon hit realities. My wonderful girlfriend let me know in the kindest possible way that I would have to find somewhere else to stay. It was hard but we are still friends, even now. I slowly realised that London was not open and free but cellular and layered and divided into sealed, often antagonistic, units. You were allowed to say what you liked but that did not mean anyone would hear you. And by the mid 1970s my hero Robert was doing some very strange things, horrible paintings, of which I did not approve, although now I am much more sympathetic - he's a human being, not a prophet...did you see his Exoskeletonshrouds?

The artists at the Staple Gardens Studios arranged a number of group exhibitions and Leo devised a piece of performance art for the opening night of one of them. He collected together a quantity of the raw materials, and detritus, of art production. When we had finished installing the show, about twenty minutes before the opening, he leaned 8ft lengths of 2x1 inch timber at 45 degree angles between each artist's contribution and then scattered bags of studio rubbish, screwed up drawings, rags, empty paint tubes and tins on the floor in front of the exhibits. By about 6.45 a reasonably large, slightly perplexed, crowd had arrived, claimed their first glass of wine and huddled in the centre of the room: no one daring to traverse the barrier of rubbish in front of the work. Suddenly Leo appeared in the entrance and began to play his flute. It was not tuneful or beguiling background music but a mad staccato, a loud avalanche of rasping and shrill notes that demanded attention. He then turned and began hopping and jumping anti-clockwise around the exhibition room, delivering a cacophonous benediction to each artist's work. In turn we followed him, first grabbing the dividing length of 2x1 and then the other rubbish in front of our work. By the time he had completed his circuit of the room all twenty of us were following him, our arms full of detritus and the lengths of 2x1 timber dragging behind us like long stiff hairless tails. Five students from the University followed after us with brooms, feather dusters and glass cleaner to give a token final polish to complete this ritual cleansing. We all followed Leo out of the gallery and into the chill of the Southampton night where everything, including Leo's flute, was thrown into the back of a van. Then, after a pause, we all processed back into our show.

We had, I suppose, expected to be greeted by applause, or at least a stunned silence, but our return went almost completely unacknowledged by the assembled crowd. They were now engrossed in their own conversations or anxiously searching out a second or third glass of wine. I never heard anyone, not even the exhibiting artists, ever mentioned this remarkable performance again. I think it was this lack of response that convinced Leo that making art was probably not for him. By the start of 1981 his father had developed and expanded his legal practice into a large financial and property consultancy and was able to entice his wayward, but very able son (he had achieved a 1st in his law degree), back to the West Country. It was at this time that Leo reverted to his Sicilian name of di Faccia, and adopted the family motto of “Non esisto io, ma sono”.

But, although I am sure that I was not alone in hoping that he had given up the flute, I was soon delighted to learn that he had not entirely abandoned his interest in art. In fact, having given up all thoughts of making anything himself, he became an active enthusiast for art and a supporter of artists. Throughout the 1980s and '90s Leo would appear in my life two or three times a year. While I was struggling with the impossibility of reconciling an intellectual and artistic life with subsistence - getting by, just scraping a living, my confidence and my youthful ambitions slowly crumbling to dust - my friend appeared more affluent and self-assured every time we met. He seemed to be developing into an expert in art theory and aesthetics. With his ever widening array of contacts in the interconnected worlds of art, finance and law, he was also becoming a confident and successful operator at many levels in the business of art. Always dressed in a tweed suit, the colour of bright copper that almost matched his hair, he became a common sight at art gallery private views, artists open studios and the VIP nights of art fairs around the world. I never attended any of these functions but I suspect that many who did would remember him without knowing quite who he was. From his conversation I understood that although he liked to keep art dealers at something of a distance, he had developed close relationships with many of the most prominent artists of the day. Through his own knowledge and his contacts he advised them on legal, investment and property matters. No money ever changed hands ("just small gifts") but in this way he assembled an extensive collection of major works of art. After a long day in London, pursuing and developing these interests, he would appear, without warning, at the door of my council estate flat in Kennington, usually after ten in the evening, often clutching two bottles of his favourite Nero d'Avola or, when he was especially excited about something, a bottle of Grappa. He would talk long into the night, with the sounds of the city, traffic, drunks, my neighbours and distant music, so often in the background. As the evening progressed, more than once he looked around my room and said:

"Peter, behind every successful artist's career is a well managed investment and property portfolio - I know you don't have any family money, which would have helped, but why don't you buy this place? You could get it for 19k with the tenant's discount, it'll be worth half a million in a few years, believe me".

I would tell him I thought his suggestion was immoral, that council property belonged to the people, it was social capital not an asset to be annexed by individuals - and anyway who would ever be able to pay thirty times an average worker's income for a small flat? He would shrug his shoulders - "Peter, I despair, you will never learn how to be an artist" - and his look communicated a sense of desperate pity that sent a chill through me. We would then move on.

In our conversations I was always struck by his grasp of ideas and his detailed knowledge of the genealogy of modern philosophy and art theory. But I sometimes wondered if his understanding of difficult concepts was really much deeper than mine or whether he was just more adept at sorting, labelling and remembering. I would try to explain something I thought and he would immediately be able to access how my idea related to some established theory which in turn related to some other crucial concept so that our conversation, or his part of it, would spiral and soar with ideas and connections - talking to Leo was like hitting a hundred great links on the internet, but before it was invented.

It was Leo who first introduced me to the work of the great Italian conceptualist Guglielmo Achille Cavellini[1], whom he considered one of the three most profound figures of twentieth century art, and to concepts that may be key to a full understanding of the art of our time: such as hypostatization, economic determinism, cathexis, ego mapping, social power projection, stealth marketing, conceptual shadowing, rhilopia, and a hundred other ideas and theories that he fired into our conversations like pyrotechnic chrysanthemums.

I lost touch with Leo for several years, but in early 2018 he tracked me down to where I then lived, a quiet place where the landscape and my life are “a subtle shading-off of everything that is emphatic”[2]. He visited me three more times in the spring of that year. As we talked, he seemed to me to be more subdued, a little lost even, compared to the old days. He told me that he and his wife were soon going to return to the land of his birth "England is becoming too much of a little island for me, I don't feel at home like I used to". I was surprised by this. He had lived here for nearly fifty years and once told me that his father, whose first legal practice was in Palermo, had brought his family to England because Sicily had become too dangerous: "My dad told me in '92 that, if we'd stayed, what happened to Falcone and Borsellino would have happened to him, and probably the whole family". Late in 2018 I received a standard, printed, card announcing the new address of Persephone Lloyd-Jones and Leonardo di Faccia on the Strada Provinciale, Belpasso, Sicily. I wrote a short note wishing them well but received no reply until November 2019 when I got a long letter from Persephone. She told me that he was very well and that she, at least, was settling in and even finding some similarities between the conversational Italian of the Sicilians and the Welsh language of her native town of Caernarfon. One passage in her letter was surprising:

On the last three occasions that we met I recorded our conversations and, for this web site, I have transcribed the recordings that relate to two areas of my work: The Pleasured Text? and the Street photographs. Sometimes the feelings one has for old friends remain powerful but, when lives and circumstances have moved on, the desire to see them and talk with them again somehow seems to die away. I doubt very much that he will ever come to Britain again, or that I will ever visit Sicily.

PFW, Butley, The Suffolk Sandlings, December 2019 (revised, Menmuir, Angus, August 2021).

Site/Time/Sectioned or, possibly, The One True Path (detail).

1978-1981

Images and texts by P.F.WHITE (Peter Frankland White). ACTIVE: 196Os to the present. LOCATION: Europe (United Kingdom). SUBJECTS: vision, perception, location, time(s), class, power, rhilopia. STYLE: exploratory, aggregative, aleatory, attentive, punctum averse.

All material (except where otherwise acknowledged) is © Peter Frankland White, , and may not be reproduced in any form without written consent. See: Notes on Rights, Ethics, Privacy and Consent. Page design by Allpicture.